At the 2024 meeting of the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology I participated in an author-meets-critics roundtable with Cameron Buckner on his book, From Deep Learning to Rational Machines. The other presenters were Raphaël Millière and Kathleen Creel. It was a good discussion but I doubt I will ever work these comments up for publication, so I’m posting them here. Nothing that has happened in the space of machine learning models recently seems to me to have substantially undermined any of these points. Even quite “sophisticated” deep network models, such as ChatGPT-4o, struggle to overcome the challenges that plagued earlier architectures. Having learned nothing, we seem grimly fated to re-wage the connectionism-classicism wars of the ’90s. However heated that past rhetoric might have been, it was still to some degree an academic debate. No longer. This time the arguments are amplified by the vast amounts of capital (and, therefore, political power) staked on the success of ever larger-scale DNNs. As I briefly suggest at the end of these comments, philosophic discussions of machine learning systems should acknowledge that they are taking place in a new epistemic and rhetorical environment and take as their point of departure the material conditions and economic interests that determine how and where these systems are deployed.

Imagination is a powerful deceiver: Commentary on Buckner, From Deep Learning to Rational Machines

The plan of Buckner’s book is ambitious. He aims to establish two main claims. The first is that deep learning-based artificial neural networks (DNNs) can, when suitably configured and trained, explain a wide range of human and animal cognitive faculties. The second is that the networks that can accomplish this considerable feat will also conform rather closely to proposals about mental content and structure made by a number of historical empiricist philosophers. Together these make up a sophisticated and spirited defense of a particular form of empiricism dubbed “DoGMA” for “Domain General Modular Architecture.”

As the book’s chapter titles indicate, the target capacities of interest include perception, memory, imagination, attention, and social cognition. These are all meant to constitute “midlevel cognitive processes” (p. 48). “Midlevel” here refers to a cluster of properties: these processes are “flexible and complex, but it is difficult to force them into the mold of an explicit rule or algorithm, and the introspectable grounds of the decision often bottom out in an effortless hunch or intuition” (p. 49). How much of “everyday” cognition is exhaustively constituted by such midlevel processes is unclear, but the book proposes that a great deal of it is.

Early in the book, Buckner surveys several possible ways that computational models might be related to mental capacities generally (pp. 34-41). Much of the approach he adopts in the book fits well within the generative difference-maker approach of Miracchi (2019). According to this framework, explanations of cognitive capacities take the form of a three-part structure consisting of a model of the target capacity of the agent, a model of the computational or physical system proposed as its basis, and a “generative” model that bridges the features of these two models. The adequacy of an explanation then turns fundamentally on whether the target capacity has been specified accurately within the agent model and whether the basis model’s features can be productively related to those of the agent model.

Our focus here will mainly be on whether DNNs can explain the phenomena that Buckner ascribes to the domain of imagination. The model of imagination that DoGMA adopts is primarily sketched in Chapter 5 and parts of Chapter 6. On Buckner’s reconstruction, a Humean conception of imagination can be recruited to address a cluster of problems that Jerry Fodor posed for empiricist associationism. One of these is the Instantiation Problem: mechanistically accounting for how tokens of concept types are retrieved or generated in ways that conform to learned patterns of association. If “bell” is associated with “food,” then the mind must have some way of producing “food” tokens when “bell” tokens occur (moreover, they must be the right “food” tokens). Another is the Compositionality Problem: how new conceptual combinations can be systematically created out of already learned concepts. Hume conceived of imagination as a faculty of generating ideas (in the form of sensory imagery), and suggested it was responsible for both of these feats. When presented with “bell,” imagination carries the mind over to the idea of “food.” And the idea of “the New Jerusalem” presents us with a city with golden streets and ruby walls—something never before observed by most of us, yet still thinkable insofar as we are able to mimetically and productively imagine it using past impressions as raw material.

If this gives us a partial specification of what imagination is, showing that DNN architectures could display similar phenomena would be a partial vindication of DoGMA. Buckner argues that different network structures can solve each of these problems: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) address the Instantiation problem, while more sophisticated attention-driven Transformers contribute to solving Compositionality.

I should say that I am not at all sure about Buckner’s solution to the Instantiation problem. As I understand it, Fodor’s point is that Hume needs a theory of how associations get implemented by the mind, and imagination cannot do that work since there is no way simply by inspecting a token of “bell” to know that it should be followed by a token of “food.” The history of past associations for other tokens of “bell” is not inscribed on this token in any way, hence it cannot be accessible to the faculty of imagination. And even if tokens of “bell” did somehow come labeled with their history of associations, that fact itself would need the same kind of explaining (see esp. Fodor 2003, pp. 123-7). The problem is showing how a history of statistical links becomes causally relevant to current thought.

GANs, however, do not solve this problem. Simplifying wildly, when appropriately trained they take us from a representational space abstracted from exposure to images of category instances to newly generated images of the same. Mapped into cognitive language, this is akin to moving from an abstract conception of BELL to an image of some bell or other. We might understand this as capturing a way we can use our imaginations, for example in response to the prompt: “Picture to yourself a bell.” An account of that particular faculty is interesting, and it plausibly counts as one form of imagination, but it isn’t addressing the specific problem that Fodor poses for Hume.[1] Imagistic instantiation or visualization is one thing, implementation of associative relations is another.

Some of Buckner’s strongest and most provocative claims about the capabilities of DNN architectures center on multimodal transformers such as CLIP, which is embedded in the DALL-E product line, and other popular text-to-image (TTI) platforms (Radford et al., 2021). Of these, he says: “Dall-E and its successor transformer-based systems DALL-E 2, Images, Midjourney, and Parti reflect perhaps the most impressive achievements of compositionality in artificial systems to date, because the images they produce depend upon the syntactic relations holding among the words in the prompt” (p. 220).

–Revelation 21:9-10

These systems promise to truly usher in Hume’s New Jerusalem: the paradise of compositional semantic comprehension applied to any novel combination of terms or ideas one can entertain. Many popular demonstration images (and videos such as those produced by OpenAI’s Sora) paint a rosy portrait of their capabilities. In the burgeoning literature on TTI transformers, the degree of semantic comprehension of compositional constructions is empirically established in a number of ways, including via benchmarks of visual question answering. At the simplest level, though, we can immediately verify whether the generated visual images match the content of the phrasal input. Once we do so, squinting a bit through the dazzle, it remains true that “without explicit relations to meld the component latent factors together, the representations generated by these DNN-based methods will still lack the ‘glue’… that can fuse together truly novel combinations of latent factors in a coherent way” (p. 219).

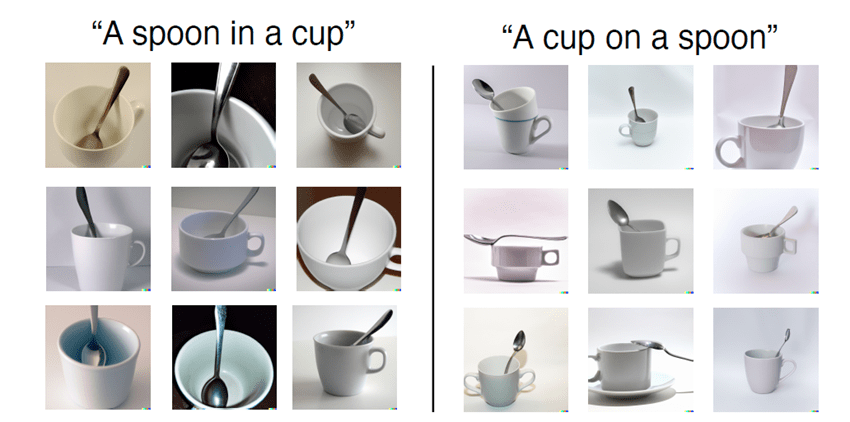

It has been argued for some time—a necessarily elastic description given the pace and opacity of work in ML—that CLIP-style multimodal models perform poorly on compositional relationships. Lewis, Nayak, Yu, et al. (2023) tested a baseline pre-trained CLIP model on three image generation tasks: adjective-noun combinations (“red cube”), two-object Adj-N conjunctions (“red cube and blue sphere”), and order-sensitive relations (“cube behind cylinder”). Contrary to what one would expect if CLIP had a fully general suite of compositional capacities, these tasks dissociate. On the bright side, single Adj-N prompts pass at above 92% for training, validation, and generalization splits, with most errors involving the property rather than the object. Two-object binding is more challenging, however, with training being 27.02% accurate and generalization 31.4%, with errors split between objects and attributes. Performance on order-sensitive relations was worst of all, with only 26.8% of training being accurate and 0% of generalization.

Attempts have been made to see how far these architectural limitations go. Zhang and Lewis (2023) evaluated an instance of CLIP that was trained exclusively in a visual “block world” containing only a sphere, cylinder, and cube and the relations front, behind, left, and right. When fed 10,000 such image-label pairings, baseline CLIP still struggled to distinguish “cube behind sphere” scenarios from “sphere behind cube” and other distractors. Training split performance was 26.76% accurate, with validation split accuracy at 15.06% and 0% accurate on the generalization split. Various forms of fine-tuning of baseline CLIP pushed the training set results higher, but validation and generalization remained at the floor. They then looked at variants of CLIP that change the form of the text embedding model. Among the most promising of these are models using BERT, but even here performance was uninspiring. The BERT-embedded model did poorly in the training split (6.49%), improved on validation (43.70%), and cratered on generalization (0.50%). Most distressingly, fine-tuned versions were perfect on training but failures (0%) on all other splits.

Such results have been qualitatively replicated and hence are unlikely to be flukes. Conwell and Ullman (2023) probed DALL-E 2’s ability to generate correct images for descriptions of scenarios involving two kinds of relations: physical (near, on, tied to, hanging over, occluding, etc.) and agentive (pulling, hitting, helping, touching, etc.). Sentences were created involving objects and agents standing in these relations, and then used to generate 1350 images. The images and prompt sentences were rated for whether they matched by a pool of human raters. The average image-picture agreement was only 22.2% across all prompts, with agentive prompts scoring better than physical ones. Some relations (touching, helping, kicking) scored around 40%, while the remainder fell below. And as the authors note, these high scores may reflect the training data: “child touching a bowl” is easy, while “monkey touching an iguana” is hard. Successful matches are slightly correlated with the internally calculated CLIP similarity score between the prompt sentence and the image. This indicates that measured task difficulty is reflected in the architecture itself.

Examples like this could be multiplied. Kamath, Hessel, and Chang (2023) tested 18 types of vision-language models (including several CLIP variants) on a newly curated set of images depicting simple pairwise spatial relations. Almost all of the models scored at or near chance, and none came close to human performance, despite the fact that some of them perform extremely well on the VQAv2 benchmark, often cited as an index of visual reasoning abilities. Tellingly, vector arithmetic on the internal representations of images in CLIP suggests that its poor performance derives from the structure of these representations: evaluating mug on table – mug under table + bowl under table should be closer to bowl on table versus bowl under/left of/right of table, but this was rarely the case. This gives further evidence that the internal structure of the model is insufficient to the task.

Studies like these suggest that even when fed optimal data (a massively simplified visual and symbolic training set), tested on uncomplicated objects and relations, and given the benefits of many common tricks for performance tweaking (scaling, renormalization, fine-tuning), the underlying architectures struggle with grasping fundamental relational structures in language and space.

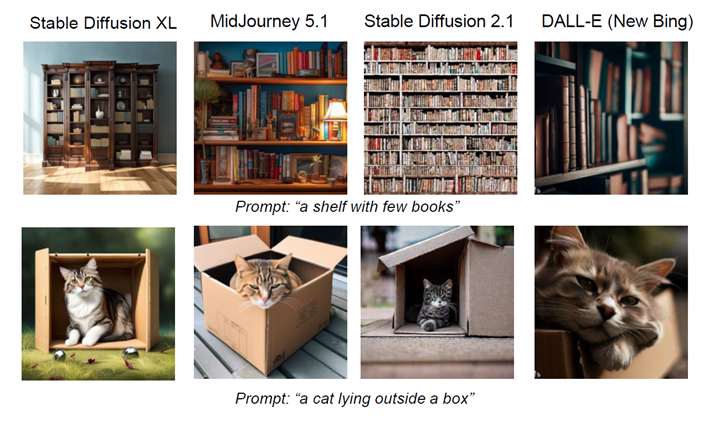

The process of finding such error patterns in TTI models has even been ingeniously automated. Tong, Jones, and Steinhardt (2023) built a system called MultiMon that automatically searches for, classifies, and creates new instances of erroneous behavior by any product based on CLIP. MultiMon’s processing pipeline first scrapes a large corpus of sentences for pairs that, based on their semantics, should not produce the same output but do, as determined by the cosine similarity of their CLIP embeddings. For instance, “table with few cups”/“table with many cups” and “cup to the left of bowl”/“cup not to the left of bowl” should not produce highly similar images and hence should have different similarity scores. It then queries a language model (either a GPT variant or Claude) to provide possible labels that cover the kinds of failures it detects. Finally it asks the language model to produce new examples of the same labeled type. This pipeline uncovered a number of systematic failure points in TTI systems, including: failure to capture negation, ignoring quantifier and numerical differences, ignoring thematic roles (the “bag of words” problem), mangling spatial and temporal relations, ignoring different kinds of action state or action intensity, and ignoring subject identity (gender, age, etc.). These failures can be expected to apply across all CLIP-embedded platforms (DALL-E, MidJourney, and Stable Diffusion).

It is furthermore no surprise that these models’ performance also suffers when prompted with more demanding constructions. Leivada, Murphy, and Marcus (2023) tested DALL-E 2 with sentences exemplifying binding and coreference (“the man paints him” vs “the man paints himself”), comparatives (“the bowl has more cucumbers than strawberries”), negations (“a tall woman without a handbag”), ellipses (“the man is eating a sandwich and the woman an apple”), ambiguity (“the man saw the lion with binoculars”), and distributive quantifiers (“there are three boys and each is wearing a hat”). None of these cases were consistently rendered correctly—no prompt category reached more than 50% right. While this study is small and can only be regarded as a pilot experiment, it is not encouraging that semantically loaded syntactic relations are so poorly dealt with.

A final example: large multimodal models also struggle to combine other forms of simple task performance. Images can also have marked constituent structure: in particular, multipanel images have clear distinctions between subimages placed within the same frame. Billboards, posters, and other ads, comics layouts, newspapers, webpages, and many other everyday media make use of this framework for information display. People can compare content across panels, select panels that match or fail to match the others, and generally process these displays fluently. While these images are culturally laden, parsing them correctly is an index of compositional understanding insofar as understanding the subparts of the image should entail understanding the whole. Fan, Gu, Zhou, et al. (2024) benchmarked human performance against that of several vision-language models (LLaVA, mniGPT-2, GPT-4V, Gemini Pro Vision, etc.) on a collection of 6600 triplets of images and questions, including both synthetic and real-world instances. Humans, unsurprisingly, perform perfectly. The very best performance of the LVMs (Gemini Pro Vision) tops out at an average of 71.6% for synthetic data and 72.3% for real-world data, followed by GPT-4V. All other models perform at chance. While this is better than in studies of linguistic compositionality, there remains a significant performance gap with respect to imagistic compositionality.

To summarize, then: much of the most recent work looking to fractionate and study the capabilities of TTI-trained DNNs indicates that they do not have the resources to solve the Compositionality problem. Since humans do, this particular DNN architecture cannot explain this capacity. Optimists about “pure” DNNs won’t be dissuaded, I expect; some studies have hinted that varying the training data in the right way can get CLIP-style systems closer to human performance (Yuksekgonul, Bianchi, Kalluri, et al., 2023). It’s important to recall another constraint on this style of empiricist project, however, which is that the training data should be a plausible match for the sort of experience humans undergo (see Buckner’s nice discussion on pp. 142-51). Tweaking the training set until we find the desired conclusion may violate this stricture.

In the present state of things, then, everyday human imagination looks unlikely to be explained by any known style of Transformer architecture. But I should add that I am unsure anyone has a grasp on what that state actually is, given the clouds of secrecy shrouding the heavily capitalized private research fiefdoms that govern these technologies. Whatever the machine learning mandarins promise, it remains to be seen whether the road to the New Jerusalem is paved with deep networks.

References

Conwell, C. & Ullman, T. (2023). A Comprehensive Benchmark of Human-Like Relational Reasoning for Text-to-Image Foundation Models. Mathematical & Empirical Understanding of Foundation Models (ME-FOMO @ ICLR) Kigali, Rwanda.

Fan, Y., Gu, J., Zhou, K., Yan, Q., Jiang, S., Kuo, C-C., Guan, X., Wang, XE. (2024). Muffin or Chihuahua? Challenging Large Vision-Language Models with Multipanel VQA. arXiv:2401.15847

Fodor, J. (2003). Hume Variations. Oxford: Clarendon.

Kamath, A., Hessel, J., & Chang, K-W. (2023). What’s ‘up’ with vision-language models? Investigating their struggle to understand spatial relations. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

Leivada, E., Murphy, E., & Marcus, G. (2023). DALL·E 2 fails to reliably capture common syntactic processes. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100648.

Lewis, M., Nayak, N., Yu, P., Merullo, J., Yu, Q., Bach, S., & Pavlick, E. (2024). Does CLIP Bind Concepts? Probing Compositionality in Large Image Models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2024, pp. 1487–1500.

Miracchi, L. (2019). A competence framework for artificial intelligence research. Philosophical Psychology, 32(5), 588–633.

Radford, A., Kim, J.W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., & Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. International Conference on Machine Learning.

Tong, S., Jones, E., Steinhardt, J. (2023). Mass-Producing failures of multimodal systems with language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

Yuksekgonul, M., Bianchi, F., Kalluri, P., Jurafsky, D., Zou, J. (2023). When and Why Vision-Language Models Behave like Bags-Of-Words, and What to Do About It? International Conference on Learning Representations.

Zhang, K., & Lewis, M. (2023). Evaluating CLIP’s Understanding on Relationships in a Blocks World. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, pp. 2257-2264.

[1] Not to belabor the Fodor exegesis, but this turns on a significant difference Fodor sees between Hume’s own views on cognitive architecture and almost every contemporary position, including connectionism. See esp. pp. 130-1, where he describes both connectionist and classical solutions to the Instantiation problem.